*Look at footnote [2] for full citation.

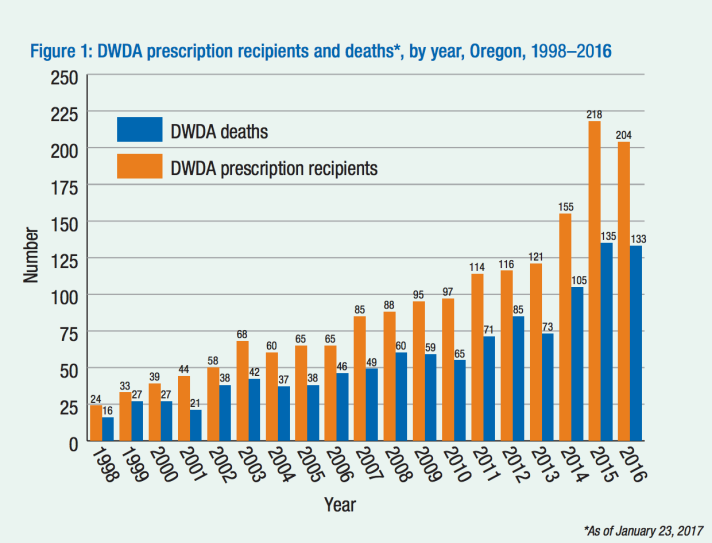

Oregon’s Death with Dignity(ORS 127.800-995) allows terminally-ill Oregonians to end their lives through the voluntary self-administration of lethal medications which has been prescribed by a physician. Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act has been in effect for the past twenty years. Since its implementation, access to using the rights the law gives an individual has been difficult due to obstacles from opponents of physician-assisted suicide. Court cases have delayed implementation, qualification and the process of obtaining drugs have caused inequalities of patients, and rising drug cost endanger access to the act.[1] Despite all of these struggles, the law is still in effect and is currently a template for other states who are writing their own Death with Dignity laws. Each year, more and more patients are taking advantage of the right the law gives them.

The law is intended to give terminally ill patients more control over the end-of-life choices. Through this law, patients have the liberty to die on their own accord. Most patients choose to end their life because of the lost autonomy and dignity and not being able to “engage in activities making life enjoyable.”[2] By choosing to use physician-assisted suicide, they are taking control over the quality of their own life.

To qualify and obtain a prescription for the lethal drug, there are several qualifications and steps. The basic qualifications include that the patients has to be 18 years old or older, a resident of Oregon, and must be terminally ill with only six months or less to live. The prognosis then has to be confirmed by two physicians. To get a prescription, the patient has to request verbally and in writing the drug with a waiting period of at least 15 days in between.[2] Another obstacle in the process is verifying mental competency. In certain cases, a psychiatrist has to sign off that a patient has the mental capability to make the decision to decide to end their own life. The final step of taking the medication has to be self-administered.

The physician also has to comply with certain rules. This protects him or her from being prosecuted for illegally assisting in suicide. Physicians have to report any prescription they give to the Oregon Health Authority. Pharmacies also have to know the intended use of the drug they are dispensing and have the right to refuse to dispense the drug. There are also certain forms that have to be filled out after the patient’s ingestion of the drug and subsequent death.[2]

Under the law, The Oregon Public Health Division has to create an annual report of all patients who received prescription through the law. The detail report compiles information from patients and doctors including information on demographics, trends, health reasons, medication used, and other information for keeping the law free of abuse. All of the reports are made available to the public.[2]

The path using physician-assisted suicide has been long and arduous with many opponents. During the 1990s in the US, there was a movement of legislative expansion on end-of-life choices and rights. In 1990, the US Supreme Court ruled in Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health that a competent person has a constitutionally protected right to refuse any medical treatment. At the same time, several states started to propose death with dignity bills. Most of them did not make it very far in the process of becoming a law. In the early 1990’s, Oregon State Senator Frank Roberts who had cancer introduced three physician-assisted suicide bills. None of these bills got out of committee, but proponents of physician-assisted persisted.[3] In 1993, Oregon Right to Die political committee was created. The group started to write a physician-assisted suicide bill. The group filed a citizen’s initiative that went on the ballot as Measure 16.[4] Oregon residents passed Measure 16 in 1994 with 51.31% of voters voting that terminally ill adults could obtain lethal medication. However, the law was not put into use until October 1997 due to an injunction from Lee v. Oregon.

The first legal challenge to the Death With Dignity Act came quickly after Measure 16 passed in 1994. In Lee v. Oregon, the plaintiffs were doctors, patients, and residential facilities who were arguing that the Act violated the First Amendment, Fourteenth Amendment, and federal statutes.[5] They specifically believed that equal protection and due process rights, religious freedom, and the American Disabilities Act, Rehabilitation Act, and the Religious Freedom Restoration Act were all being violated. The law was placed on a temporary injunction while being heard by the courts. The injunction was lifted in 1997 after the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed the case, and the injunction was lifted.5 This setback did not deter opponents of the Act. Soon after, a new measured was brought to voters which would repeal Death with Dignity. Measure 51 did not pass with 59.91% of voters voting to keep the Death with Dignity Act. After these two significant hurdles, the law was able to finally be implemented.

However, in 2001, the act faced another chief opponent: US Attorney General John Ashcroft. He issued a directive which allowed federal agents to investigate and prosecute physicians who prescribe federally controlled drugs to terminally ill patients die. He argued that the physicians were violating the Controlled Substances Act. Ashcroft believed that physician-assisted suicide was not a “legitimate medical purpose,” and thus violated of the Controlled Substances Act.[6]

Eventually, the case made its way to the US Supreme Court in 2005. In Gonzales v. Oregon(formerly Oregon v. Ashcroft), the court ruled that the Controlled Substance Act does not define general standards of state medical practice, and the attorney general does not have the authority to overrule state prescription drug laws. Since 2006, the Death With Dignity Act has been unchallenged and widely supported by Oregon voters.[8]

Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act is often referred to informally to as the Right to Die Act. However, while implementing the law, it becomes self-evident that in some cases it is a privilege and not a right to utilize this law. Patients who participate in physician assisted suicide are predominantly white, educated, and middle to upper class.

Demographics of Oregon[10]

| White | African American | Asian | Hispanic or Latino | |

| 2000 | 77.90% | 6.64% | 6.33% | 6.82% |

| 2010 | 76.09% | 6.29% | 7.14% | 9.39% |

* Data collected from the U.S. Census

Demographics of those who use the law over the past 19 years

| Race | White | Hispanic | Asian | African American |

| 96.5% | 1.1% | 1.3% | 0.1% |

*Data collected The Oregon Public Health Division.

From the table above, it is evident there is a significant difference in the percentage of white residents(76.09% in 2010)[10] and the percentage of white patients who have used the law(96.5%).[2] There are systematic reasons for this inequity. It is a nationwide trend that minorities have less access and adequate healthcare. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, minorities receive worse medical care and less of it on compared to compared to whites patients. Quality and access is about about 40% less.[11] The data goes on to illustrate that African American patients have the most inferior care of all groups. The process for obtaining the drug is arduous. If minorities already receive a lower quality of care, they are also more likely to not have this option be a possibility for them.

However, there are confounding factors for the disproportionate category of people who use the law. Distrust between white doctors and minorities are another reasons why minorities do not participate as frequently in physician-assisted suicide. Black patients are wary of the health care system and do not trust physicians due to the unethical treatment of black men in the Tuskegee experiments. In the experiment, researchers withheld information from black patients that they had syphilis and did not provide them with treatment.[12] There also differences in public opinion of physician-assisted suicide dependent on race.

There are also clear economic disparities in those who choose to utilize the law. Patients are well-educated with 46.1% of patients having a baccalaureate or higher degree.[2] Almost everyone who uses the law has insurance with 54% having private insurance and 44.6% having Medicare, Medicaid or other governmental insurance.[2] The complicated process of obtaining the drug is primarily to blame. Those who are less economically stable and do not have health insurance are not going to have access to two different physicians plus a psychiatrist. The price of the drug could hinder some from participating in physician-assisted suicide. Many private insurers, Medicaid and Medicare cover the costs of the drug. The most common type of lethal medication used is Seconal.[2] In 2009, the price of a lethal dose was less than $200. In 2015, the same dose costs $1,500 and by of 2016, it cost $3,000.[13] For those who do not have insurance, the cost of going to through the process might deter them.

Over the past 20 years, there has been no evidence of abuse or misuse of the law.[14] The safeguards make it extremely hard for any abuse or misuse to happen. Since two physicians have to agree, this prevents patients who do not qualify from getting a prescription from abusing the law. Plus, when needed a psych exam has to be conducted. At the same time, the safeguards can be seen as too stringent. In 2016, only 133 people had a prescription under the law.[6] In the same year, 8,076 patients died from Malignant neoplasms(cancer) in Oregon.[15] While it is impossible to set a quota on how many patients should choose physician-assisted suicide. It is very apparent that for almost all of cancer patients, physician-assisted suicide is not an option for either personal or practical reasons.

The drastic increase in the price of lethal drugs threatens the future of the law. If the drugs become too expensive, insurers including Medicare and Medicaid might stop covering it. The price of the drugs have increased because more states are implementing Death with Dignity Acts, and pharmaceutical companies see the potential of making more money. One part of reform would be to control drug prices so more patients can have access to this end of life option.

As the population continues to age and live longer, more bioethical debates will ensue on who should and should not use Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act. Alzheimer and Parkinson’s Disease has become part of the conversation. The last stage of Alzheimer’s is brutal and arguably inhumane with a loss of all speech, trouble controlling bowels and bladder, no sense of location, and forgetting how to swallow. There needs to be reform on how to expand the qualifications. Alzheimer patients do not qualify because they need to be competent within six months of their predicted death. A new clause needs to be written so those with Alzheimer’s can make the decision earlier on when they are competent about the end-of-life care.

Oregon was the first state to implement a physician-assisted suicide law. Since other states were able to see the implementation and how there have not been misuse or abuse, they were more willing to implement their own laws. In 2017, six states and Washington D.C. have extremely similar Death with Dignity laws.[9] In the coming years, we will see this trend to continue to grow.

[1] Purvis, Taylor E. “Debating death: religion, Politics, and the oregon death With dignity Act.” The Yale journal of biology and medicine 85.2 (2012): 271.

[2] Oregon Death with Dignity Act Data Summary 2016. Rep. Public Health Division, Center for Health Statistics, 22 Sept. 2017. Web.

[3] Kandra, Lindsay R. “Questioning the foundation of attorney general Ashcroft’s attempt to invalidate Oregon’s Death With Dignity Act.” Or. L. Rev. 81 (2002): 505.

[4] Humphrey, Derek, and Mary Clement. Freedom to die: People, politics, and the right-to-die movement. St. Martin’s Press, 2000.

[5] Lee v. Oregon, Nos.95-35804, 95-35805, 95-35854, 95-35948 and 95-35949 (1997)[6]

[6] Supreme Court Considers Challenge to Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act: Gonzales v. Oregon and the Right to Die. Rep. Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, 30 Sept. 2005. Web.

[7] Gonzales v. Oregon, 546 U.S. 243 (2006)

[8] Stutsman, Eli. 2013. “Twenty years of living with the Oregon Death with Dignity Act.” GP Solo 30(4): 48

[9] “Death with Dignity Acts – States That Allow Assisted Death.” Death With Dignity. N.p., n.d. Web. 01 Sept. 2017.

[10] “QuickFacts.” U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts selected: Oregon, http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/OR.

[11] US Department of Health and Human Services. “Disparities in healthcare quality among racial and ethnic minority groups [Fact sheet].” Washington, DC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011).

[12] Jacobs, Elizabeth A., et al. “Understanding African Americans’ views of the trustworthiness of physicians.” Journal of general internal medicine 21.6 (2006): 642-647.

[13] Dembosky, April. “Pharmaceutical Companies Hiked Price on Aid in Dying Drug | State of Health | KQED News.” KQED Public Media for Northern CA, KQED, 22 Mar. 2016, ww2.kqed.org/stateofhealth/2016/03/22/pharmaceutical-companies-hiked-price-on-aid-in-dying-drug/. Accessed 3 Nov. 2017.

[14] Nelson, Roxanne. “Death With Dignity in Oregon: No Evidence of Abuse or Misuse.” Medscape, Medscape Medical News, 20 Sept. 2016, www.medscape.com/viewarticle/869023.

[15] TABLE 6-8. Number of deaths by cause and month of death, Oregon residents, 2016.” Oregon.gov, Oregon Health Authority, 2016, http://www.oregon.gov/OHA/PH/BIRTHDEATHCERTIFICATES/VITALSTATISTICS/ANNUALREPORTS/VOLUME2/Documents/2016/Table608.pdf.